Leena Manimekalai’s Searing Portrayal Of Violence Against Women In ‘Maadathy’ Is Powerful Cinema

Filmmaker Leena Manimekalai’s 2019 feature film ‘Maadathy’ is about patriarchy and misogyny within the Dalit community.

There is a haunting, unsettling quality to Leena Manimekalai’s ‘Maadthy: An Unfairy Tale’ (2019) from the first frame. Though most of the film takes place out in the open, amidst lush fields, verdant forests and a flowing river, there is a sense of dread all through. The viewer is left guessing behind which tree, around which turn of the narrow path, or the bend in the river does danger lurk – the danger of men.

It is this dread which Manimekalai makes flows from Veni to the viewer whenever Yosana is outside. In an inversion of the usual trope, there is a sequence of Yosana secretly gazing at Panneer (Patrick Raj), a young boy from the community, swimming naked in the river. But instead of it being sensuous the scene turns sinister as the camera cuts to the close up of the girl—what awaits her when the camera pulls back?

In an uncanny coincidence, I could draw parallels between Maadathy and Prayers For The Stolen (2021) by Tatiana Huezo Sanchez set half the way across the world in rural Mexico. Here too the surroundings are forests, hills and rivers, and every time the young Ana steps out her mother Rita is as worried as Veni. In Prayers…the predators are gun-toting child traffickers, where being beautiful is a curse, mothers cut their daughters’ hair and rub dirt on their smooth skins to make them ‘invisible’. Sanchez too makes the viewer feel the dread every time the girls are out, gaily running in the fields or take a lonely road.

Manimekalai makes this foreboding of violence, when it inevitably comes, even more unbearable by its casualness. For the men, brutally assaulting a woman, crushing her spirit, wounding her for life, doesn’t seem to be any more than lighting another beedi or pouring another glass of arrack. The film exposes the patriarchy and misogyny in the Dalit community, the layers of ‘caste’ within it, and how in the end the most oppressed and violated are always the women.

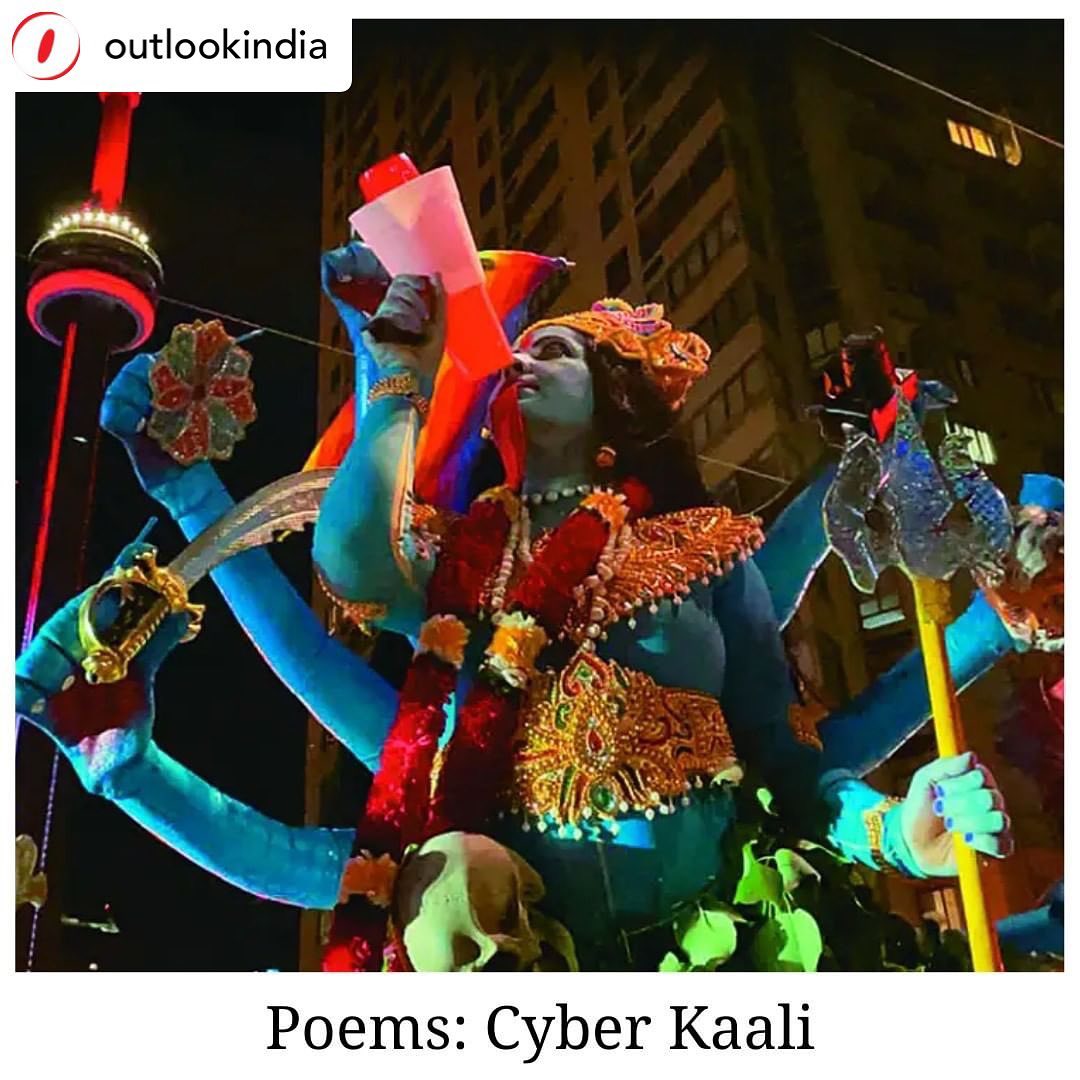

Kaali is the Woman-@outlookindia

“Bureaucracy in India is always a mouthpiece of the government.

Whose Sentiments Got Hurt Anyway?

There have been myriad responses to this release on social media, with some people highlighting Kali’s significance as a deity who rejects social norms & pressures. It is worth noting that Kali is often depicted with her tongue sticking out, which is interpreted as her rejecting the moralistic pressures of society and her mockery of the people who defend them without examining their own desires and shadow selves.

On the 2nd of July, Toronto-based poet and film-maker, Leena Manimekalai announced the launch of their new film ‘Kaali’ at the Aga Khan Museum. The film was announced as a part of the week-long Rhythms of Canada festival at the museum.

In the poster, a person with long hair and various adornments such as a crown and jewelry across their chest, seems to portray the blue-skinned deity, Kali. They are wearing prosthetic arms and are carrying accouterments like a trident and a sickle made of cardboard. In another of these arms is a rainbow flag (signifying the queer rights’ movement), while the person themself sips on a cigarette.

There have been myriad responses to this release on social media, with some people highlighting Kali’s significance as a deity who rejects social norms & pressures. It is worth noting that Kali is often depicted with her tongue sticking out, which is interpreted as her rejecting the moralistic pressures of society and her mockery of the people who defend them without examining their own desires and shadow selves.

Others, however, issued threats against Manimekalai, who was born in Tamil Nadu. For instance, Saraswathi, who is the leader of a Hindutva group in Tamil Nadu, Sashti Sena Hindu Makkal Katchi, threatened to ‘bash up’ Manimekalai with slippers via a viral video, if the latter didn’t take the poster down in 4 days’ time.

Saraswathi’s video went viral around the 5th of July and the Selvapuram police began their investigations into the threat soon after, ending in Saraswathi’s arrest.

Several complaints have also been filed with the police, demanding punitive action against Manimekalai, in various parts of the country. For instance, the Hindu Suraksha Manch and the United Trust of Assam have filed an FIR in Dispur, Assam.

The Indian High Commission too urged Canadian authorities to take the promotional material down, showing how the State’s solidarity often takes the form of enforcing respectability politics, instead of encouraging democratic discourse through free speech and media expression. Following this, the Aga Khan Museum has apologised for ‘hurting religious sentiments’.

Ironically, this reminds me of that Dabur Fem ad that tried to position itself as inclusive by portraying a queer couple engaged in the rites of Karwa Chauth. While several in the community welcomed this, even as others (including myself) rejected it as an attempt to rainbow-wash casteist and colorist practices as queer-friendly, the brand itself took the video down after Hindutva advocates complained about hurt religious sentiments.

The moral of the story to me is that positioning ourselves as ‘well-behaved queers’ will never earn us the liberation nor the validation that we so desperately seek from a society that espouses values that reject and alienate us in systemic ways.

In a display of misogynistic and queerphobic algorithmic bias, Twitter too took down the poster, prompting Manimekalai to ask: “Will Twitter withhold the tweets of the 200000 hate mongers?”

In response to the Hindutva-led reprimand of Manimekalai’s work and related promo material, Art Historian and Associate Professor at UC Berkeley, Sugata Ray, shared a lithographic print from the collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The print was a wrapper for cigarettes manufactured as part of the Swadeshi Movement (that boycotted foreign-made/branded goods as part of India’s fight against British imperialism).

Ray translated a few lines from the label as saying: If you care to improve the manufacture of swadeshi [national} products, if the welfare of the nation’s poor laborers is your concern, if you have a sense of good and bad, then O Hindu brothers, smoke these Kali cigarettes.

Soon after, an anti-caste Twitter user also asked if the famous Mangalore Ganesh Beedis will also be re-branded in the face of the imposition of Brahmnical values on various deities that have been part of various regional cultures and pagan groups in the Indian subcontinent.

Which begs the question: Whose Sentiments were hurt anyway? And whose sentiments do we care about? Art may not be an imitation of life in many ways, but its censorship certainly seems to be.

Celebrating the Plurality of Hindu Iconography & Tradition: In Defense of Leena Manimekalai

Hindus for Human Rights (HfHR) stands in unequivocal solidarity with filmmaker Leena Manimekalai, who has faced a barrage of threats and censorship for the poster advertising her upcoming documentary “Kaali,” which shows Goddess Kali smoking a cigarette and holding a pride flag. This poster has upset a subset of Hindus who seem unaware not only of the cultural practices of those who worship Kali, but of the incredible diversity inherent to Hindu traditions more broadly.

The true inner strength of Hindu religious traditions is that different communities have found spiritual inspiration in different ways. It is common in many parts of India for devotees of Kali to offer alcohol and meat as naivedyam (food offerings)—including at Kolkata’s Kalighat temple, which is one of the 51 holiest sites for Shakta Hindus. At the Viralimalai Temple in Tamil Nadu, cigars are offered to Lord Murugan. These practices are part and parcel of a diverse Hindu tradition, and Manimekalai has every right to explore these traditions through her art. Furthermore, many LGBTQ+ Hindus look to our traditions and sacred iconography as affirming their own dignity and identities, and the pride flag that Kali holds in the film poster is a way of acknowledging the deity’s meaningfulness to LGBTQ+ Hindus.

Furthermore, it is deeply troubling that the Aga Khan Museum and the Toronto Metropolitan University have apologized for collaborating with Manimekalai and revoked her opportunity to showcase her work. Twitter has also made the unconscionable decision to take down the image of her film’s poster. In kowtowing to the Indian government’s unreasonable demands for censorship, these institutions have betrayed the basic democratic right to freedom of expression while giving power to Hindu nationalists who seek to silence critics and artists.

As Hindus who believe in freedom of expression, the diversity and plurality inherent to Hindu traditions, and the sanctity of Mahakali, we fully support Leena Manimekalai and call on our fellow Hindus to stop all hateful threats and trolling. The Indian government is on an overt mission to make India a Hindu nation, and an integral part of this mission is a sustained effort to present Hinduism as a homogenized monolith. The world must not support this dangerous endeavor.