#Freedomofexpression -leenamanimekalai

To Leena Manimekalai

In a very holy land

In a very pious place

One hundred thirty crore people live

Sensitive, religious, courageous and non-sensuous.

We get hurt

And rightly so

When a polymorph smokes

And a strange man named Zubair

Says the truth

We are very decent people

We kiss in private

We kill in public.

We worship our goddesses.

We are fine with female infanticide

We are very tolerant

No one ever has been lynched here

for their names!

We are champions of freedom of speech!

We never celebrate violence.

Three days of peace conclave happened

In Haridwar

Under the holy presence of some

Holy men

No one has called for genocide there.

We, one hundred and thirty crore people

are very soft-hearted,

You must agree, Leena!

We boo our girls for being a lesbian

and we are the highest dowry payer!

This is the story of a noble country

You must understand, Leena!

How dare you, Leena!

How can your goddess work in a pride march!

About the poem: This poem is in solidarity with Leena Manimekalai who is getting a lot of flak for the poster of her movie.

Moumita Alam is a poet from West Bengal. Her poetry collection The Musings of the Dark is available on Amazon

My Kali is queer: Resisting the homogenization of Hinduism

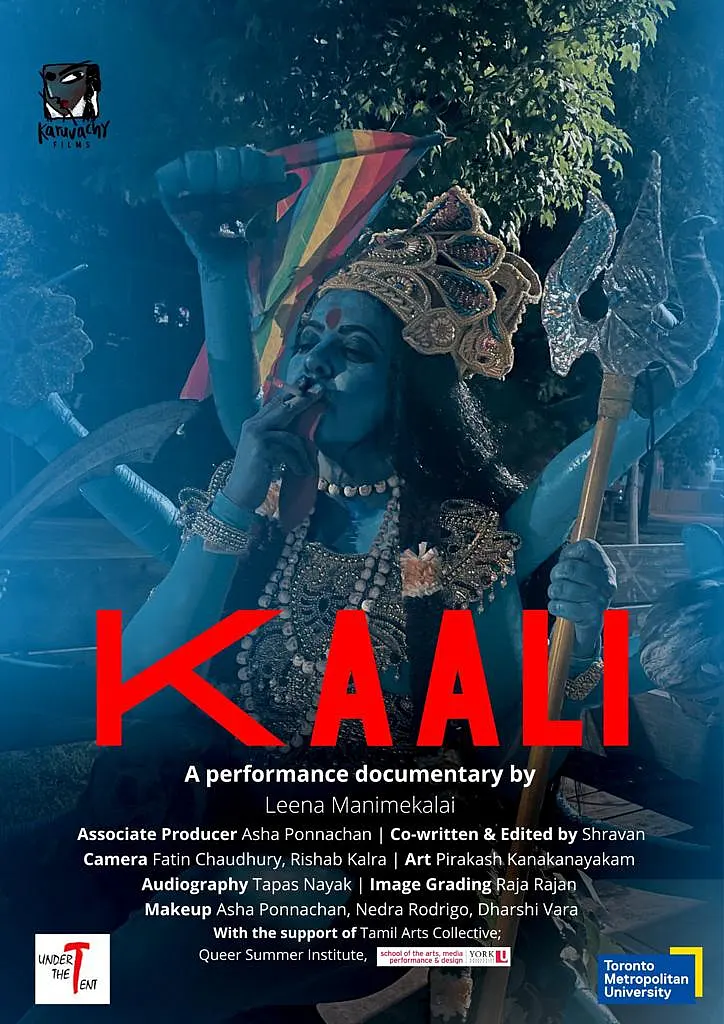

Manimekalai calls “Kaali” a “performance documentary” — a personal and poetic meditation on the female divine. In a six-minute excerpt shown at a multimedia exhibition in Toronto last week, Mother Kali, Hinduism’s powerful goddess of death and the end of time, wanders through a pride festival in Toronto at night. She observes groups of people out on the town, takes a subway ride, stops in a bar. People take selfies with her. In the last frame, she is on a park bench where a man gives her a cigarette. The poster for the film shows the goddess smoking a cigarette and holding a pride flag.

The Aga Khan Museum and Toronto Metropolitan University caved in to pressure from the Indian government and issued apologies for screening the film. Twitter removed Manimekalai’s tweet showing the film’s poster. Manimekalai is wanted for arrest for “hurting religious feelings” in Assam, Uttarakhand, Haridwar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and several other states and has received numerous death and rape threats.

In an email Manimekalai said the controversy had made it impossible for her to return to India. “My safety is a big question mark now and I feel totally derailed to be honest. But I don’t want to bow down, and so I’m fighting with full power.”

Manimekalai comes from a South Indian community that worships the Goddess Kali as “a pagan goddess” who “eats meat cooked in goat’s blood, drinks arrack, smokes and dances wild,” the filmmaker told The Guardian.

Manimekalai, who identifies as bisexual, says, “My Kali is queer. She is a free spirit. She spits at the patriarchy. She dismantles Hindutva. She destroys capitalism. She embraces everyone with all her thousand hands.”

Someone unfamiliar with Hinduism might say Hindus are justified in their outrage. It’s important to understand, however, that the film and its poster are in line with a long tradition of diversity of Hindu practice and belief and immense personal freedom in one’s relationship with the divine.

An Indian member of parliament, Mahua Moitra, defended the film, saying, “To me, Kali is a meat-eating, alcohol-accepting goddess. I am a Kali worshipper. I am not afraid of anything. Not your goons. Not your police. And most certainly not your trolls.” Moitra is now facing criminal charges, too.

Kali first appeared in Indian culture as an Indigenous deity before being absorbed into the Brahminical traditions and Sanskrit texts in the present-day form “as a dangerous, blood-loving battle queen.” Hindu Goddesses are at the same time fierce warriors against evil and injustice and unconditionally loving and protective, and Kali’s devotees consider her the Divine Mother of all humanity.

Neither cigarettes nor queer pride is forbidden in Hinduism. Hinduism is historically very open toward sex and sexual difference. Innumerable stories in Hindu Scriptures tell of same-sex relationships, children born of same-sex relationships and characters — some of them gods — who are gay, queer or trans.

The South Indian Goddess Mariamman is often offered alcohol, and animals are sacrificed for her. The Guyanese “Madrassi” community comprises Hindus who worship Devi (the Mother Goddess) in all her forms, particularly Mariamman and Kateri Amma. “We firmly believe that devotion to Amma is subjective, and she comes to each of us in a unique way,” Vijah Ramjattan, president and founder of the United Madrassi Association in New York, told me. The community’s first Madrassi Day parade in 2017 featured an LGBTQ artist and dancer, Zaman, perform as the goddess Sundari.

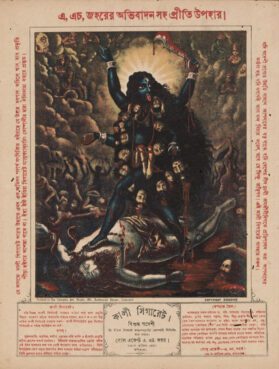

‘Kali Cigarettes’ advertisement, Calcutta, India, circa 1885-90, Lithograph. Image courtesy British Museum

Hindu deities smoke, drink, get high and sometimes eat meat. It is very common for alcohol, meat and even cigarettes to be offered to deities, particularly Kali. As the writer Shuddhabrata Sengupta explains, in the late 19th century, a Kali brand of cigarettes was produced in Calcutta.

One advertisement read, ‘If you care for the development of ‘svadeshi’ [homegrown Indian] products, if you feel responsible for the poor, miserable, working people of this land, if you can truly distinguish between good and evil, then, o Hindu brothers, you must use these ‘Kali’ cigarettes!”

Walking through the narrow labyrinthine lanes of Varanasi, one of the holiest Hindu cities, it’s hard to miss the government-run “bhang” stands selling cannabis in the form of cookies and cakes, or as a drink. Most holy men in the city take bhang, local swamis told me, to deepen the experience of meditation and communion with God. Drugs have been part of Hinduism since prehistory; Lord Soma, the Vedic god of healing and plants, is named for a hallucinogenic which was offered to god and drunk by priests.

The extreme and egregious reaction to “Kaali,” the film, and its poster denies the Hindu idea that we all have tendencies towards goodness (satva), passion (rajas) and lethargy (tamas) and that our job is to ensure that the best parts of us win. We are allowed our mistakes because even the gods err.

And gods are everywhere: I grew up with my gods and goddesses on everything around me: my lunchbox and water bottle, clothes, vehicles, toys, movies and movie posters. We were taught to think of god in very intimate ways: Our parents and teachers were god, but so were spouses and lovers. I was called Krishna in my family because my mother and her sister were both mother to me, and Krishna, too, had two mothers. A friend told me his uncle was called Krishna because he had a wife and a mistress; Krishna, too, is known for having several wives and lovers.

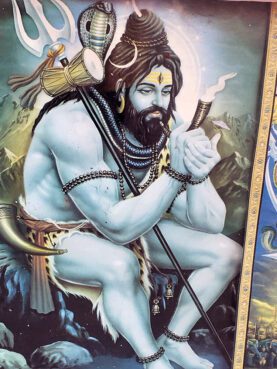

An image of Lord Shiva lighting a chillum at Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi, India. Photo by Sunita Viswanath

I always appreciated this intimacy Hindus have with the divine that allows us to choose a deity for our devotions, to shape that deity according to our own desires. We come to the god of our choice as we are, and god welcomes us.

The violence and misogyny Manimekalai is facing is unconscionable, but the larger issue for Hindus is that her critics are bent on creating a homogenized Hinduism robbed of its glorious diversity. If there is a story of injustice behind every deity in India, the injustice today is that the deities themselves are being constrained, reduced, strangled. This homogenization favors Brahminical and Sanskritized texts and practices and erases the ways that non-Brahmin communities worship.

But the two issues are essentially the same: This homogenization favors male brutality. The Hindu nationalist version of the god Rama is warring, angry, with no Sita, his female companion, by his side. The Hindutva Hanuman is blood-red and furious, instead of the embodiment of love and sacrifice. Meanwhile they whitewash Kaali of everything that makes her fierce.

In the impassioned words of Moitra, “Neither Lord Ram nor Lord Hanuman solely belongs to the BJP,” she said, referring to India’s ruling Hindu nationalist party. “Has the party taken the lease of Hindu dharma? … [The BJP] is a party of outsiders that tried to impose its Hindutva politics but was snubbed by the electorate. BJP should not teach us how to worship Maa Kali.”

Kali, she concluded, “urges us all to resist the BJP’s attempt to “impose its agenda of Hindutva (Hindu nationalism) and thrusting its monolithic views” for the sake of the country.

This starts with giving a young filmmaker the right to express herself freely through her art.

(Sunita Viswanath is a co-founder and executive director of Hindus for Human Rights. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

FIRs in Delhi, UP Against Leena Manimekalai for ‘Kaali’ Documentary Film Poster

New Delhi: The Delhi and Uttar Pradesh police have registered cases against documentary film Kaali and director Leena Manimekalai for allegedly hurting religious sentiments and the Indian high commission asked the Canadian government to take down all “provocative material” in the film.

The cases come after controversy erupted over the film’s poster, which shows a woman dressed as a Hindu goddess smoking a cigarette, with a pride flag in the background. The film was released in Canada.

Super thrilled to share the launch of my recent film – today at @AgaKhanMuseum as part of its “Rhythms of Canada”

Link: https://t.co/RAQimMt7LnI made this performance doc as a cohort of https://t.co/D5ywx1Y7Wu@YorkuAMPD @TorontoMet @YorkUFGS

Feeling pumped with my CREW❤️ pic.twitter.com/L8LDDnctC9

— Leena Manimekalai (@LeenaManimekali) July 2, 2022

According to the Indian Express, the police received several complaints against the poster and Canada-based Manimekalai. One of the complaints was filed by BJP leader Shivam Chhabra, who stated, “Movie director Leena Manimekalai posted a tweet on June 2 about her documentary film ‘Kaali’ and shared its poster. In her tweet, she said the poster was released at Canada Film Festival and that she’s excited about the film…the poster shows Kaali Maa (goddess) smoking a cigarette. The goddess is holding a Trishul in one hand and an LGBTQ flag in the other hand.” A member of a group going by the name ‘Gau Mahasabha’ also filed a complaint.

According to news agency PTI, a senior Delhi police officer said on Tuesday that from the contents of a complaint and the social media post, prima facie an offence under sections 153A and 295A of the IPC was made out and a case registered against Manimekalai at the Intelligence Fusion and Strategic Operation (IFSO) unit of the Special Cell.

While Section 153A deals with the offence of promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, Section 295A relates to deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class.

A probe in the matter has been launched, the officer said, adding the case was filed on the basis of a complaint received from a lawyer.

In Lucknow, the FIR was registered at the Hazratganj police station against Manimekalai, producer of Kaali Asha Associates and editor Shravan Onachan on Monday night. The FIR was lodged under sections 120B (criminal conspiracy), 153B (imputations, assertions prejudicial to national integration) and 295 (injuring or defiling place of worship with intent to insult the religion of any class) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), and sections 66 and 67 of the Information Technology(IT) Act, the police added.

Earlier, the Indian High Commission in Ottawa urged the Canadian authorities to take down all “provocative material” related to the film.

Manimekalai shared the poster on Twitter on Saturday. Members of the Hindu right soon objected, with the hashtag ‘Arrest Leena Manimekalai’, and allegations that the filmmaker was hurting religious sentiments.

A statement issued by the High Commission of India in Ottawa on Monday said that it had received complaints from leaders of the Hindu community in Canada about the “disrespectful depiction” of Hindu gods on the poster of the film showcased as part of the ‘Under the Tent’ project at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto.

“Our Consulate General in Toronto has conveyed these concerns to the organisers of the event. We are also informed that several Hindu groups have approached authorities in Canada to take action,” the statement read.

Manimekalai, who was born in Madurai in Tamil Nadu, on Monday said she will continue to use her voice fearlessly while she is alive.

“I have nothing to lose. Till the time I live, I wish to live with a voice that speaks what I believe without fear. If the price for that is my life, it can be given,” Manimekalai wrote in a Twitter post in Tamil in response to an article on the controversy.

“The film is about the events during Kaali’s strolls through the streets of Toronto city one fine evening. If they watch the movie, they will put the hashtag ‘love you Leena Manimekalai’ rather than ‘Arrest Leena Manimekalai’,” she added in reply to another article.

Manimekalai, who made her feature directorial debut with 2021’s Maadathy – An Unfairy Tale, isn’t the first filmmaker to find herself in a controversy over religious references.

In 2017, for instance, filmmaker Sanal Kumar Sasidharan courted controversy over the title of his Malayalam film Sexy Durga, which explored religious divides in Kerala society. The film was later rechristened S Durga. Last year, Prime Video’s political saga Tandav was at the centre of trouble for a scene depicting Lord Shiva in a college theatre programme. The scene was eventually dropped and the streamer issued an apology.

(With PTI inputs)

Note: This article was originally published at 3:45 pm on July 5, 2022 and republished wat 9:25 pm on July 5, 2022 with details of the case filed in Uttar Pradesh.

Leena manimekalai: Kaali பர்ஸட் லுக் சர்ச்சை; `இந்தக் காளி இன்னும் பேசுவாள்’- விளக்கமளித்த இயக்குநர்

ஒரு மாலைப்பொழுது, டோரோண்டோ மாநகரத்தில காளி தோன்றி வீதிகளில் உலா வரும்போது நடக்கிற சம்பவங்கள் தான் படம். படத்தைப் பார்த்தா `arrest leena manimekalai’ ஹேஷ்டேக் பதிவிடாம `love you leena manimekalai’ ஹேஷ்டேக் பதிவிடுவாங்க

சுயாதீன திரைப்பட இயக்குநர் லீனா மணிமேகலை `செங்கடல்’, `மாடத்தி’ போன்ற தன் படங்களால் கவனம் பெற்றவர். சமீபத்தில் அவர் வெளியிட்டுள்ள தனது டாக்குமென்டரியின் பர்ஸ்ட் லுக் தற்போது இணையத்தில் வைரலாகி வருகிறது. அதற்கு சிலர் கண்டனம் தெரிவித்து, `arrest leena manimekalai’ என்ற ஹேஷ்டேக்கைப் பதிவிட்டு வருகின்றனர். இதுகுறித்து லீனா மணிமேகலையிடம் பேசினோம்.

“காளி – வேட்டை சமூகங்களோட கடவுள். ஊருக்கொரு பிடாரி, ஏரிக்கொரு அய்யனார்னு சொலவடை உண்டு. நம்மூர்ல பச்சைக்காளி, பவளக்காளி, கருங்காளின்னு பிடாரி தெய்வமா,முத்தாரம்மன் கோயில்கள்ல குலசேகரப்பட்டணங்களில் – காளியை பார்க்கலாம். அந்தக் காளி டோரோண்டோ நகரத்தில வலம் வந்தா என்ன நடக்கும்னு செய்து பார்த்தது தான் என்னுடைய `காளி’ படம்.

உலகத்திலேயே அதிக குடியேற்றம் நடக்கிற நகரம் டோரோண்டோ. கிட்டத்தட்ட எல்லா இனங்களும் வாழற ஊர் இது. இங்க இருக்கிற `யோர்க் பல்கலைக்கழகம்’ ஒவ்வொரு வருஷமும் ஒரு சர்வதேச திரைப்பட இயக்குநரை தேர்ந்தெடுத்து முழு உதவித்தொகை கொடுத்து வரவழைச்சு மேலதிக பயிற்சியை எடுத்துக்கொள்ற வாய்ப்பையும் மாஸ்டர்ஸ் டிகிரியையும் வழங்குது. 2020-ம் வருடமே என்னைத் தேர்தெடுத்தருந்தாலும் pandemic, #metoo defamation case அடிப்படையில் பாஸ்போர்ட் முடக்கம் – பிறகு அந்த வழக்குகளை முறியடிக்க போராட்டம்னு பல காரணங்களால தள்ளிப்போய் 2022-ல தான் கனடா வர முடிஞ்சுது.

கனடா முழுக்க சினிமா படிக்கிற மாணவர்கள்-ல சிறந்தவர்கள் சிலரை தேர்தெடுத்து கனடா நாட்டின் பன்முக கலாசாரத்தை பற்றிய படங்களை எடுக்கிற முகாமில் பங்கெடுக்க `டோரோண்டோ மெட்ரோபாலிடன் பல்கலைக்கழகம்’ அழைப்பு விடுத்தது. அந்த முகாம்ல கலந்துக் கொண்டு என் பங்களிப்பா நான் எடுத்த படம் தான் `காளி’. காளியா நடிச்சி இயக்கி தயாரிச்சிருக்கேன்.

ஒரு மாலைப்பொழுது, டோரோண்டோ மாநகரத்தில காளி தோன்றி வீதிகளில் உலா வரும்போது நடக்கிற சம்பவங்கள் தான் படம். படத்தைப் பார்த்தா `arrest leena manimekalai’ ஹேஷ்டேக் பதிவிடாம `love you leena manimekalai’ ஹேஷ்டேக் பதிவிடுவாங்க. அவ்வளவு இன வேற்றுமைகளுக்கு மத்தியிலும் வெறுப்பை தேர்ந்தெடுக்காம நேசத்தை தேர்ந்தெடுக்கிறதைப் பற்றிப் பேசறா இந்தக் காளி. இன்னும் பேசுவாள்.” என்றார்.