Thank you Green Majority Radio for the space #Blackhistorymonth it is

From the Margins: A conversation with Writer and Filmmaker Leena Manimekalai

Leena talks to TC on her journey as a filmmaker, the recent backlash she faced and her Artist Residency at UofT’s Jackman Institute.

My films are always imperfect, raw, genre jumping, straight from the voices of the community that spoke truth to power.- Leena

Catch screenings of Leena’s Maadathy and Kaali on March 15, 2023 7pm at Innis Town Hall, Toronto. For more info visit: uoft.me/8QG

Gender and social justice are key themes that you explore in your films. How did your childhood and life experiences shape your views on these themes?

Gender is nothing but indentured labour in brahmanical patriarchy. My mothers and grandmothers were exploited as both labouring and reproducing bodies to maintain land, ethnic purity and caste pride. I wanted to break that chain of slavery. I protested every given gender role and expectations. My thirst for justice is my thirst for being a person of my choice and owning up my story. My childhood was my violent rupture from subordination and thrusted identities. Nothing scares the system than a female existence with agency, voice, opinions and sexuality. Every single force would want to crush my existence. My resistance to be crushed defined my life experiences and evolved my politics.

Leena on location for Parai (2004), the first ever Tamil documentary where Dalit women speak about sexual harassment on camera. Excerpt from Parai available here

Many of your work features rural cultural practices. What is your fascination with them and are you using your medium as a means to document these traditions?

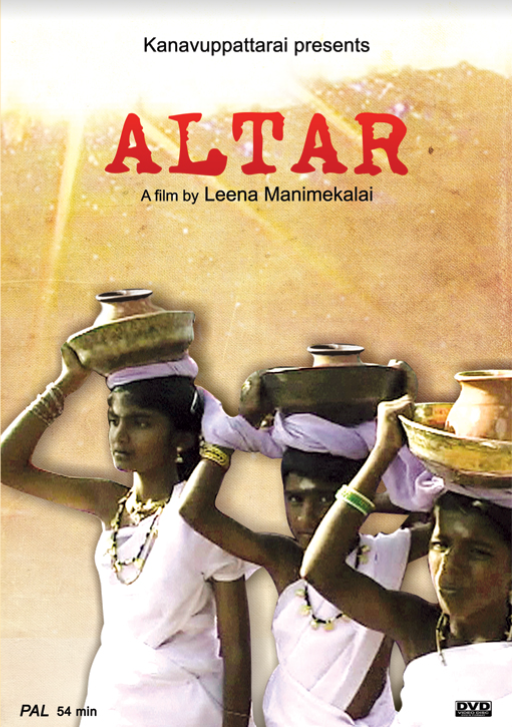

Leena on the location in Karur, Tamil Nadu for her documentary பலிபீடம்/Altar (2005)

I am a daughter of western ghats. My native village under the slopes of Sathuragiri mountains is where Tamil anarchist poets Siddhars were believed to have lived over 1000 years. Srivilliputhur the town where I was brought up has a temple for Poet Andal and it stands tall in Tamilnadu emblem. I come from an agrarian family and I grew up worshipping small gods and deities. I am all at once காட்டு நெல்லி (kaatu nelli), மானம்பாரி (maanampaari), எள்ளுச்செடி (elluchchedi), புளியம்பழம் (puliyambalam), மாவூத்து (maavooththu), வரையாடு (varaiyaadu), குற்றாலச்சாரல் (kuttralachcharal). I am nothing if you remove the Mariyamma’s spirit from me. I am walking in my ancestors’ feet and they include all the wild trees of செண்பகத் தோப்பு (senbagath thoppu)

Cover of பலிபீடம்/Altar (2005) a documentary intervention exploring the child marriage practices that exists within the Kambalthu Naicker community in central Tamil Nadu. Excerpt from Altar available here

Not coming from a filmmaking background, what was the biggest revelation that you had when you started off in the Tamil film industry?

I am a first generation filmmaker. My father did not have a wikipedia page. I am coming from a place where female representation is less than one percent as authors in cinema. I had to throw myself into the abyss, trial and error, be banished and burnt, to find my way out. I found my voice when I realised I have to create my own image and not a perceived one. One thing I know for sure is that, nobody would have gotten to know the stories, if I had not filmed them. My filmography and bibliography is my ஒற்றையடிப் பாதை (ottraiyadip paathai). I had to cross, burn, and destroy hundreds of fences to find it.

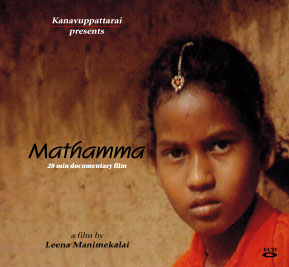

Mathamma (2003) captured a peculiar practice of devoting girl children to the deity of the folks of Arundhatiyar community, Mangattucheri village near Arakkonam, Chennai. Excerpt from Mathamma available here

Contrary to many others who begin their filmmaking journey with either short features, feature films or even advertising, your first work, Mathamma, was a documentary, As was many of the work that followed. What was it about this style of filmmaking that appealed to you?

I grew up watching films that profited by insulting and humiliating women. Growing up,I could never identify with the women shown on silver screens. It was all feudal masochist in nature. The industry practices are also hierarchical, misogynist and casteist. I was a misfit in the film industry. I picked up filmmaking from the streets. Revolution in digital technology democratised the resources and I got access to cheap cameras and software. I was hardly twenty when I made my first documentary. I went in my scooty wound with microphones to film my people. All I learnt is from them. My films are always imperfect, raw, genre jumping, straight from the voices of the community that speak truth to power. None of my films were ‘projects’. They were my ‘calling’ and one led to another. My life as a filmmaker is the story of my total submission to the truths I found, love and solidarity to my people and their struggles and fierce resistance to censorship. Everything else is a bonus.

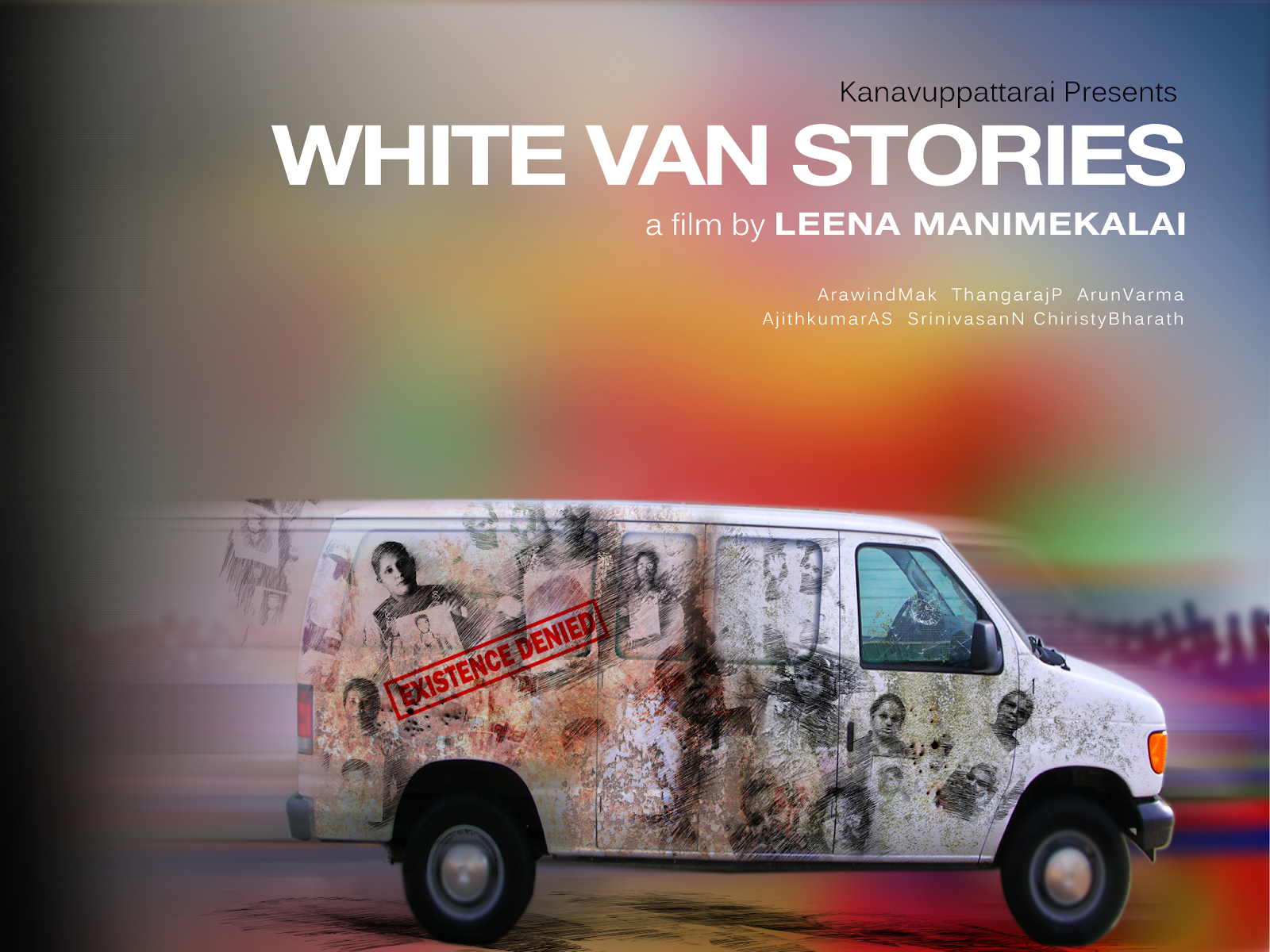

Documentary cover of White Van Stories (2013) captures the plight of families of missing persons in Sri Lanka. Promo available here

Probably the most risky documentary that you have made is “White Van Stories”. It’s been 10 years since, but the topic of missing persons in Sri Lanka remains a matter of concern and families are still awaiting answers. Can you tell us how this project came to be and the experience of filming it? Have Jaya, Rasiya & Sandya, and the family members featured in the film, found any answers?

They will never find answers. They protest to keep their questions alive. They are the only voices still lingering out of the whole war fought for Tamils’ right to self determination. When I attended the first ever Ilakkiya Santhippu held in Jaffna, post war, I stayed back and volunteered in the steering committee of activists. We were mobilising the families of the disappeared from North, East, South and the Hills for a potential protest in Jaffna around the then, UNHRC Commissioner, Navi Pillai’s visit. I travelled throughout Sri Lanka meeting the leaders, families and the allies. That journey was life altering, preparing me to risk everything to document their stories.

I was stopped, interrogated, my tapes confiscated and at one point sent back to India by the Sri Lankan Military Forces. I had my own ways to return to filming. Thanks to the warrior women and their resilience like Vetrichelvi and others, that the film was made. They fed me, protected me and trusted me with their stories. My risks were nothing before the mountains they move everyday.

Catch episodes of our latest podcast ‘Identity’!

- Shakthi / Theatre, Intergenerational Trauma and Australian Tamil Identity

- Identity Podcast: Anuk/ Language, Grief and Tamil Community

- Maral/ Art, Belonging & Armenian-Iraqi-Canadian Identity

- Identity Podcast: Shuba/ Music, Feminism and Dual Identities

How the film got a broadcast opportunity was serendipity. I had cut a trailer and tweeted – tagging the Channel Four team. In a few hours, I got an invitation to fly to London, edit the material into different lengths and broadcast them. It was a high voltage experience broadcasting the film while the British PM Cameron was attending the CHOGM sessions in Colombo. It was surreal to witness the characters in the film blocked from meeting Cameron right after the broadcast and him taking the train to Jaffna and finally being able to meet and hear them. It was one week of broadcast activism. I was under high security protection until my return to India. All that the Tamil community offered was additional constitutional ban, malicious hate propaganda, slander and hate.

Leena’s first feature film Maadathy (2019). Maadathy trailer available here

How did the transition from being a documentary filmmaker to a feature filmmaker come to be? And why did it take till Madathy to get there?

First ever film in the history of cinema is factual cinema. I respect both factual and fictional cinema. Subjects I choose, decide the genre of storytelling. Tamil society considers only hyper masculine, hyper real masalas as cinema. I belong to the transnational legacy of cinema. Kurosawa, Kiarostami, Agnes Varda, Chantel Akerman, Maya Deren, Ritwik Ghatak, G Aravindan are my ancestors. Rare Tamil films like Aval Appadithan, Pasi, Veedu did earn my respect but I am largely uninspired by Tamil Cinema.

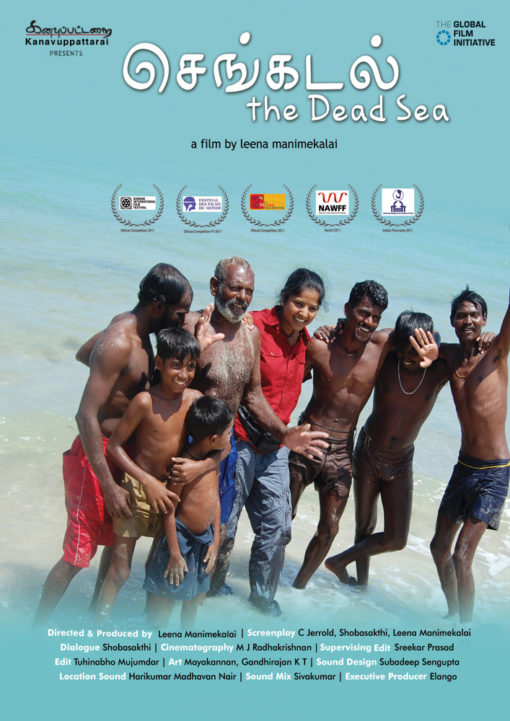

Leena on location for Sengadal (2011) in Danushkodi, Tamil Nadu, filmed in the Cinema Verite structure. It was yet another daring work that follows the lives of Tamil fishermen and the atrocities that they face at the hands of the Sri Lankan Navy. Trailer available here

You may guard this closely but can you give us a glimpse of what your process is like from the time you have an inspiration all the way to having that final script/screenplay ready to be filmed?

Total surrender is my process. I keep myself widely open throughout the process of seeking, finding, discovering and creating. When I could handle my ‘knowing’ and not define my ‘feeling’, I create good art. Writing is where I build my worlds. Rest is all execution. I fail 99 times and what surfaces is just that 1 percent.

‘Kaathadi’ was your thesis project during your Master’s in Fine Arts in Film degree program at York University. It was quite an ordeal for you to get there; fighting defamation, getting your passport impounded and your perpetrator even writing to the University to pull back your visa. How supportive was York U throughout this and how did these elements shape Kaathadi?

Kaathadi is my personal memoir. It is my catharsis of being born as a shudra Tamil queer female body. I was trying to address generational trauma of a gendered existence with a hybrid film woven with poetry, dance, movement theatre, architecture/landscape, music, drama and documentary. My department at the York University, Professors and Cohort had my back and in fact rooting for me through my struggles with covid waves/lockdowns, #metoo defamation cases, passport impoundment and my legal fights. Even during the post ‘Kaali’ situation that was done as a project for TMU’s CERC Migration, my Professors at York University took initiatives and ran a signature campaign collectively with the community of artists/academicians/scholars in Canada, in solidarity with my art and fight.

But the reaction to Kaali shook my supportive ecosystem in York University too. My Supervisor stepped down a few weeks before my defence stating that his safety will be at stake. That really broke me down more than the life/rape threats and state persecution. I was assigned a new Supervisor and he took my film for legal opinion, without my consent, stating the film is too ‘sensitive’. I wrote to my dean and withdrew from my MFA program as I felt violated of my rights. Then the equity committee and well meaning feminist-queer activist Professors intervened and came on board as my supervisory committee.

Kaathadi flew with full freedom. Life wasn’t satisfied with this much and I was shattered once again with the sudden demise of my dear collaborator-composer-sound designer Phil Strong just one week before my oral defence. Kaathadi the film, the support paper of 80 pages and the oral defence was all about picking my pieces. So many births and deaths.

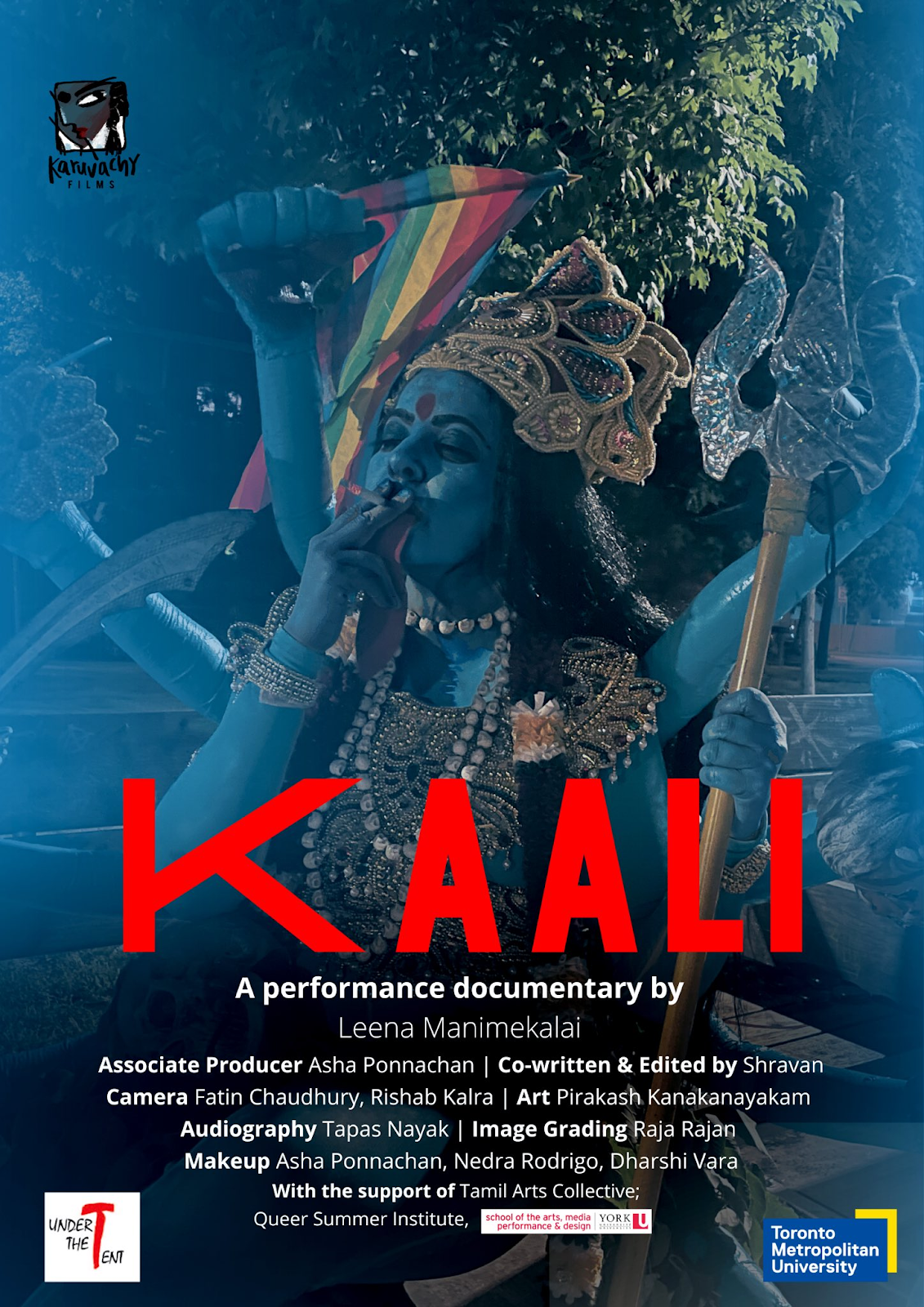

The controversial poster of Kaali (2022)

Your Kaali rattled the subcontinent. Can you explain how Kaali, a tribal goddess from rural India, fits in the narrative of exploring settler colonialism in the streets of Toronto?

I invite you to watch the film to reflect on it. In my film Kaali, Goddess Kali descends upon me and loiters in this stolen land that is also home for millions of broken people. It is a playful 9 minutes of an indigenous feminine spirit’s gaze and the returning gaze of people of various ethnic-racial-cultural backgrounds and nationalities. Sharing a smoke in the film is all about sharing humanity. It is not everyone but brahmanical patriarchal fundamentalists who were rattled. If I had portrayed Kali as their “Ma” changing their diapers they wouldn’t have rattled.

Kaali is also my commentary on how multiculturalism is maintained like a zoo in Canada. One should not forget that this country is run by “white” power where immigration is open to people who are vanquished because the country needs human resources for nation building. The only difference between American imperialism and Canadian Capitalism is gun culture and an inclination towards welfare in terms of governance.

Institutions like Toronto Metropolitan University and Aga Khan Museum, though run by public money under Canadian sovereignty, dissociated themselves from me , the minute the Indian High Commission issued a statement to withdraw their support to my film. Economy that the Indian students bring to these institutions weigh more than academic freedom and they don’t risk diplomatic relationships for that reason.

The tip of the iceberg is that North American Indians in power and positions are predominantly brahmins and stooges of hindutva but they play the victim card in the name of their colour and grab all the opportunities from historically oppressed indigenous, black and coloured populations. The institutions neither pretend nor put any effort to understand the complexities of Indianness or Tamilness but continue to posture diversity.

One of the biggest criticisms regarding Kaali, who’s seen smoking a cigarette and waving the pride flag on the film’s poster, was that you wanted to create a sensation. And that creative freedom, which comes with responsibility, was mishandled. What do you have to say about this?

This comes from the culture of victim blaming. It is no different from questioning a rape survivor on what clothes she was wearing. Always some senas or parivars or brigades will feel hurt whenever a film is out for public viewership. But democracy is not for the vigilantes to treat citizens as a flock of sheep. The Constitution of India protects the right to freedom of speech and expression to all the citizens of India. One must remember that the right to offend is also part of this freedom.

What happened in the case of Kaali is not a controversy, not a backlash, not an outrage. It was an organised campaign and orchestrated violence. This has been a pattern to the artists, activists, journalists, authors and dissenters who refuse to be part of the grand narrative of Hindu supremacy. It is so easy to blame an artist than the fascist forces who want to dehumanise and defile a living woman in the name of protecting the goddess.

“One thing I know for sure is that, nobody would have gotten to know the stories, if I had not filmed them” Leena

One of the biggest prices that you had to pay, due to the Kaali row, was that you were not able to be with your beloved grandma, Avva, during her last moments. Is the price that you pay for your voice, activism, social commentary and art, worth it?

I was severely traumatised, not being able to be with my Avva in her last days. I failed to hold my mother’s hands, grieve with her. I could not participate in the mourning with my family and folks. I will be scarred by this for my entire life. Nothing is worth this loss.

You’ve mentioned that you want audiences who view your films to enter the world that your films create and to participate in the narrative. But yet, independent films such as yours are quite inaccessible beyond festivals and limited availability on online platforms. What is the challenge here? Why aren’t such films widely available on mediums like YouTube under a pay wall?

Visibility has always been a huge challenge for indies. Filmmakers who refuse to provide ‘content’ for the market are invisibilized throughout history. Art is not a capitalistic commodity. A society should have a decency to appreciate, protect and nurture the art and the artist. Can’t expect that from a society that censors, pirates and never values a cultural worker.

Leena filming தேவதைகள்/Goddesses (2008), a documentary that captures the story of 3 ordinary women (a fisherwoman, funeral singer and a grave-digger and) living extraordinary lives going against society’s norms to live and work according to the rules they have set for themselves

Financial success is not the primary driver of films such as yours. Yet financial pressures exist both professionally and personally. How does an artist like you reconcile this and still make the art you want?

Artists work, but never become workers. They are blood banks for vampiric institutions and an insatiable public expecting them to create magically without food, safety, home, help, time or money. My meditation during my Artist Residency at UofT would also be on how artists are forced to survive in the liminal space between precarity and resistance.

My independent work has never paid me for my labour. I pay my bills by doing commissioned projects for television, teaching, lectures and mentorship. I survive as a punctured space between one film to another.

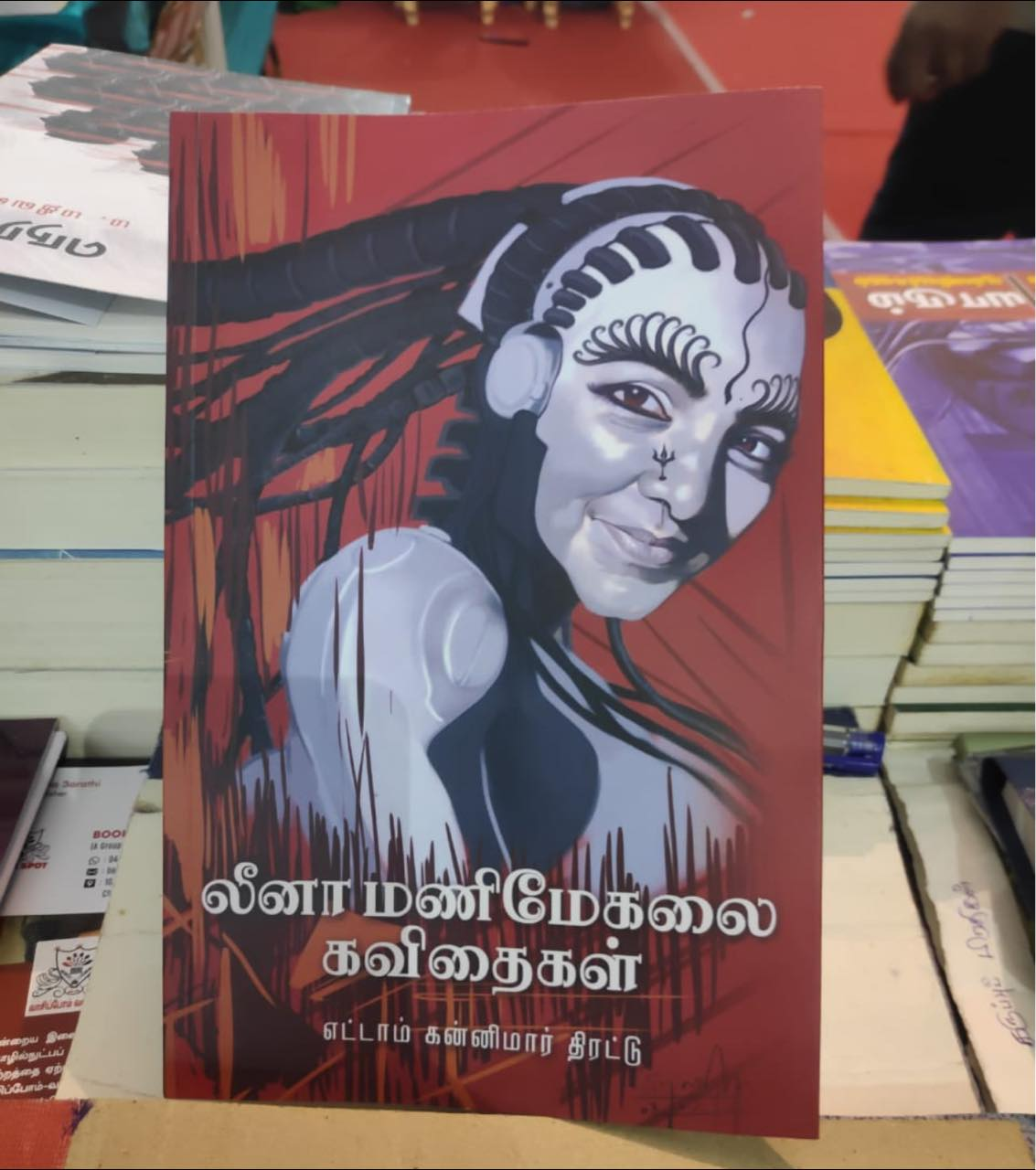

Leena’s collection of more than 500 Tamil poems was a crowd favorite at the recent 2023 Chennai Book Fair

To quickly touch upon your writing, is there anything that you are unable to express via your films that your poetry allows you to address?

I am formerly a Poet. My film practice is its extension. Both are world building exercises for me. I feel, I write, I create. I build my worlds with words, images, sounds, light, color, human bodies, landscape, wind, earth and every element of this Universe. My whole challenge is to translate my feelings to my unique world of poetry and cinema. I emote through my little creations.

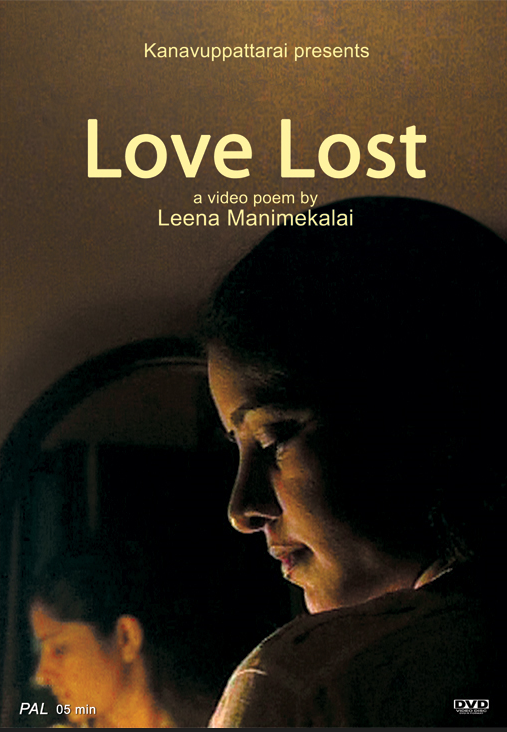

Cover from Leena’s poetry anthology தீர்ந்து போயிருந்த காதல் /Love Lost (2005). Excerpt from Love Lost available here

What’s next for you Leena and what are your goals with the Artist Residency at the University of Toronto?

It is indeed a huge honour to be named as Artist in Residence by University of Toronto. I am also an inaugural Artist in Residence of the Center of Free Expression at Toronto Metropolitan University. It is quite stimulating to interact with the scholarly interdisciplinary and artistic academic communities. So much to share, learn and unlearn. My days are packed with screenings, workshops, presentations, classroom interactions and debates.

My next is not in my hands. My multiple barrel gun is always fully loaded with feature film scripts, series, documentaries and transmedia projects. I leave it to the time fairy to trigger what and when.

“I went in my scooty wound with microphones to film my people. All I learnt is from them.” Leena

Scribbles:

A book that you are currently reading? The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schwarz Bart

A book that changed your perspective? பதின்ம வயதில் வாசித்த, பெரியார் எழுதிய, பெண் ஏன் அடிமையானாள் (Penn en adimaiyanal by Periyar)

A film that you watched recently that you loved? Spellbound by Lucrecia Martel’s entire filmography, that I happened to watch while writing my thesis

Person(s) who’ve inspired you in your creative process? The characters and communities I happened to meet for my films. They were my Shamans

A film that you recommend for someone wanting to get into filmmaking? Surrender to the process, have faith and be the open vessel. Films will get made.

A line of poetry that has been stuck in your mind? அன்பின் வழியது உயிர்நிலை (Anbin valiyathu uyirnilai – Love is the basis of life, Thiruvalluvar)

Catch screenings of Leena’s Maadathy and Kaali on March 15, 2023 7pm at Innis Town Hall, Toronto. For more info visit: uoft.me/8QG

Works of Leena available online:

Maadathy: Let the gods tell their own stories

“Nobodies do not have gods; they are gods.”

There are gods who spring to life from the blood of the oppressed. The dead, unjustly murdered come back as avenging guardians, primal in their sense of justice. This is often the lineage of “folk” gods otherised by institutionalised Vedic Hinduism. A Hinduism that is jealously guarded by the upper-caste. Director and writer Leena Manimekalai’s upcoming film, Maadathy – An Unfairy Tale tells the story of a mother goddess of the same name. But her story is also the story of the Puthirai Vannar women. Puthira Vannars are a dalit sub-caste who are considered the lowest in the caste hierarchy. They are supposed to wash the clothes of other dalits, the menstruating and the deceased: a “slave caste” says Leena. They are told to remain out of sight because even to see them would pollute the “pure”.

The director tells the story of the women made doubly invisible by caste and patriarchy through the life of one adolescent girl fighting for visibility. Speaking to the Indian Cultural Forum, Leena Manimekalai says, “The girl becomes immortalised and these folklore stories are very much part of our culture. I grew up hearing them and I felt that those stories tell my real history. Not the ones I read in textbooks. The history of nobodies is in the folklore. I found my hero from one of those stories.” Dalit oppression bans them from entering temples, from seeking the protection of a deity. “What other than stories and oral histories does the subaltern have for their solace and hope? They are nobodies. That’s my tagline; nobodies do not have gods; they are gods” she adds.

This powerful and compelling story is now facing possible censorship. The Regional Officer, Chennai of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has denied an Adults Only (A) certificate for the film that she had applied for, unless Leena makes the cuts suggested by them. Her concern for sexually exploited adolescent women from an oppressed community has been deemed “immoral”. The film is being refused certification on the grounds of “Religious Contempt, Nudity, Strong Language and Portrayal of a Minor Girl in Infatuation” Leena tells us. The film has been made with community participation with regard to the cast and the writing. “I use the language spoken by the very people whose story I am trying to tell. We don’t censor language that has rape culture ingrained in it, in our everyday lives, right? Then why sanitize it in films? CBFC has no business interfering in our creative calls. If Bandit Queen can have nudity, why not my film? Nudity is primal and when I deal with a story that expresses primal instincts, I have to portray that.”

Legal Complexities

The Cinematography Act, 1952 provides some of the guidelines for the CBFC’s functions. The Act also provides the applicant (the filmmaker) the chance to appeal against refusal of certification without modifications or the granting of a certificate other than the applicant’s preferred choice. The appeals are brought to a Tribunal hearing in an office specified by the Central Government. Leena will soon be appearing before such a Tribunal to appeal the refusal of an (A) certificate without cuts to Maadathy. The film director reminds us that the CBFC ought to be functioning primarily as a certification board, and not as a censor board.

It is a tough fight, especially for independent filmmakers who have more to lose than studios with big budgets. The principles for guidance such as the following, for certifying films are provided under the Act:

“A film shall not be certified for public exhibition if, in the opinion of the authority competent to grant the certificate, the film or any part of it is against the interests of [the sovereignty and integrity of India] the security of the State,friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or involves defamation or contempt of court or is likely to incite the commission of any offence.”

The Act appears to have gone through many amendments over the years, which seem to shift the responsibility of the board towards certification rather than censorship. Yet, the official CBFC website offers links to the 1952 Act and the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983 as references for applicants. It also provides broad guidelines for certification in a separate page on the website. The following is one such example:

“Scenes –

showing involvement of children in violence as victims or perpetrators or as forced witnesses to violence, or showing children as being subjected to any form of child abuse.”

All of this leads then to the question of why governments and/or bureaucrats need to be provided with the means to interpret films, especially those dealing with crucial social justice issues with heavy handedness? Take more such examples:

“The Board of Film Certification shall also ensure that the film

i. Is judged in its entirety from the point of view of its overall impact; and

ii. Is examined in the light of the period depicted in the films and the contemporary standards of the country and the people to which the film relates provided that the film does not deprave the morality of the audience.”

Or

“Human sensibilities are not offended by vulgarity, obscenity or depravity”

ICF spoke to Indira Unninayar, the lawyer who will represent Leena at the Tribunal hearing, to ask the many pressing questions regarding censorship and free expression. She pointed out that world over, film censoring is becoming obsolete as countries become more progressive and liberal. “The Act certainly empowers the CBFC to evaluate a film based on certain guidelines. The guidelines have some normative value which the government has placed as a benchmark for the CBFC to evaluate a film. But the purpose is not to be sitting there with the intention to chop and cut and say that I have the power to chop this thing until you make the cuts to the film.”

We also discussed the legal value of words such as “morality” “obscenity” “decency” “public order” and “religious contempt”. Morality, obscenity and decency seem to be philosophical problems. This language in these guidelines and Acts peg the fate of films on personal and subjective values. On what grounds then, can the law appeal? “Yes, their subjective nature is the reason that films run into problems. They are left to the values of the authorities” she agreed. “But that is why the Supreme Court has laid down the term “reasonable”. It should be according to the values of a “reasonable person and not a weak-willed person” which is also subjective, of course.” She explained further that there is second factor that is also taken into consideration. “Take obscenity for example, if there is a social evil – and the point of showing that is to curb that evil, the artist’s right to expression will prevail. Ultimately, yes it rests on somebody’s value system.”

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

Referring to freedom of speech as a constitutional right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a), she explained that it is subject to “reasonable restriction” under Article 19(2) of the Constitution. These are the issues that Maadathy will have to contend with at the Tribunal hearing.

Discussing Leena’s case, the lawyer continued “The Regional Officer has said that some aspects in the film are beyond credibility. It is impossible for a 15-year-old to have any infatuations, in her view.” Maadathy appears to deal with both budding sexuality in an adolescent and sexual violence. The first completely natural, the second predatorial. Asked if the portrayal of minors as having sexual desires violates any child protection laws, Indira confirmed that it doesn’t. She was also quick to point out that this is a person approaching adult-hood and not a small child.

“Similarly the RO has also refuted the title denying the possibility of how subaltern gods are believed to come to life. The fact of the matter is, people in her position aren’t even aware of such belief-systems. These are things that we will have to challenge and explain at the hearing. You also have to give examples of other films that have been passed where the courts have judged that certain scenes are shown with regard to a certain religious faith and not to titulate.” She further elaborated that they will have to refer to instances when the Supreme Court has ruled that social realties do need to be depicted in order to curb social ills. The answer isn’t a cover-up and pretending that it doesn’t exist. Depicting this is entirely up to the artist.

“It’s unfortunate that many of the authorities, especially ROs aren’t even aware of various religious rituals. When you give them the examples of court-rulings, they say that, that applies to the courts, not us. You have to even lay it out for them, that it is the law of the land and everybody is bound by it.” Unninayar also added.

“I was asked to remove texts that mentions that our folk gods have a backstory of injustice. I was accused of religious contempt. I was questioned on how I could show a minor girl in infatuation” says Leena. “They demanded that I clean the language used in the film.”

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

This is not the first time that Leena Manimekalai’s work has been subject to censorship and backlash. Her debut film Sengadal (The Dead Sea) dealt with the lives of fisherfolk and refugees in the Indo-Sri Lankan border shores. The CBFC refused to pass it fearing it would impact diplomatic relations between India and Sri Lanka. Like Maadathy the film was made with community participation. It is their stories that Leena wanted heard. It was cleared after the Tribunal’s intervention. Indira Unninayar represented her in that case too. She has also represented Anand Pathwardhan when his film faced similar censorship. “Why do they make us go to courts all the time, spend our money, energy and resources to get their senseless orders quashed and get reminded that their job is to certify and not censor?” asks Leena.

White Van Stories, her documentary on enforced civil disappearances in Sri Lanka during the war, has been screened in other parts of the world. But not in Tamil Nadu, allegedly because the Tamil Nationalists branded her a traitor for her criticism of the Liberation Tigers of Elam (LTTTE).

The Tribunal will hear Leena Manimekalai’s appeal in the next few weeks. The Indian Cultural Forum will follow up on the verdict.The stories in Maadathy need to be heard. Stories of “folk” gods are stories of dalit and adivasi assertion. Institutionalised Hinduism has made attempts to Sanskritise these gods. Those attempts cannot be viewed as “acceptance”. Rather they are a deliberate move to reinforce caste hierarchy through homogenisation. So, why shouldn’t the gods tell their own stories?

Festival Censorship is Quite Dangerous, Fascist In Motives: Leena Manimekalai

While interacting with News18.com, Leena maintained that she stands in solidarity with the three banned films and filmmakers.

Kriti Tulsiani | News18.com@sleepingpsyche2

Updated:June 14, 2017, 12:53 PM IST

A battle that filmmakers have been fighting and unfortunately, will continue to fight, is the one with the censor board. While it’s a mandate for Bollywood directors to get CBFC’s nod and certification before the film’s release, the films screened at festivals do not necessarily require a censor certificate, but a censor exemption from the Union Ministry for them to be screened.

In what has cast a cloud over the 10th edition of the International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerela (IDSFFK), the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting has denied censor exemption to three documentary films broadly dealing with Jawaharlal Nehru University protests, the Rohith Vemula incident and on the unrest in Kashmir, without citing a specific reason.

Filmmaker Leena Manimekalai, whose documentary Is It Too Much To Ask will be running in the official competition at the forthcoming film festival, took to Facebook to announce that 160 filmmakers, artists, and academics have written to Mr Venkaiah Naidu, Minister of Information and Broadcasting, urging him to “stop its censorship regime and immediately provide exemption to the films they have prevented from being screened” at the festival.

Questioning the basis for denying screening permission to these films, they’ve also highlighted that each of these films deals with “prominent political issues that have led to much discussion within the country” in the letter addressed to Naidu.

“It is also clear that the government of the day is resorting to draconian action to stifle all such political debate and indeed Article 19 of our constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of expression to every citizen of this country,” read the letter.

While interacting with News18.com, Leena maintained that she stands in solidarity with the three banned films and filmmakers.

“This whole pattern of festival censorship is quite dangerous and fascist in motives. We’ve sent the collective statement and we’ll have to wait and see,” she said.

When asked if this kind of censorship poses a threat to quality cinema, she said, “Censorship is always a threat to sensible cinema. CBFC has to be trashed and this extra-constitutional censorship has to be resisted by all means. Else what is the meaning of democracy.”

Considering that CBFC chairperson, Pahlaj Nihalani, recently warned filmmakers of the strictest action to be taken against them – if they continue to take their films to International film festivals without censor board certification, this move has further set the alarm bells ringing.

“This Modi govt decides what to eat, what to watch, what to wear and what to speak. This Pahlaj Nihalani should go back to school and learn how the international cultural scene works. He is an embarrassment to even deal with,” she said.

“No international film festival bothers about a censor certificate,” she added.

PN Ramachandra’s The Unbearable Being Of Lightness, NC Fazil and Shawn Sebastian’s In The Shade of Fallen Chinar and Kathu Lukose’s March March March are the three documentaries to have invited the wrath of the central government this time.

Whether it’s a depiction of a trouble-torn Kashmir or a narration of the students protest at JNU and its aftermath or a tale ‘too women oriented’ – the decision to ban art, in the name of censorship, requires a serious justification so that it just doesn’t end up being a bane of the lives and minds of filmmakers across the country.

Films on Lankan war in stormy seas

March 14 2017 10:33 PM

By Gautaman Bhaskaran

The civil war in Sri Lanka was a bitterly fought one between the minority Tamils and the majority Sinhalas. The Tamil-speaking population – which has its sympathisers in the people of Tamil Nadu, bound as the two are by a common language – was demanding a separate homeland in the northern parts of Sri Lanka. For 30 years, the two communities battled, ruining the economy and causing unimaginable suffering among the common people. In the end, the Tamils lost, and their leader, Vellupillai Prabhakaran, who headed a militant organisation called Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was brutally shot dead by the Sri Lankan army. The strife in terms of human displacement with one million Tamils now living outside their homeland, is only comparable to World War II.

But while so many films have been made about the Holocaust and the Nazi atrocities on Jews – with six million of them being killed in gas chambers – not many movies have been made on the Sri Lankan conflict. The most important reason is the intense hostility towards any such film – both from the Tamils in India and the Indian authorities. While the Tamils imagine every movie on the subject to be pro-Sinhala, the Central Board of Film Certification in India feels that any work even remotely talking about the Sri Lankan issue has the potential to create communal disturbance. Outside officialdom, Indian extremist groups are always targeting such cinema.

The famous Lankan auteur, Prassana Vithanage’s With You Without You – a really touching drama about a Sinhala soldier-turned-pawn-broker who marries a Tamil girl – was stopped from being screened in Chennai at the eleventh hour by Tamil chauvinists, who felt that the movie was pro-Sinhala. It was not. By no stretch of imagination, I would say.

Another film fighting it out is Sherine Xavier’s Muttruppulliyaa (Is It A Full Stop?). This is a 105-minute documentary that narrates the true story of a Tamil Tiger rebel who has a hard time raising her three children after the war ends in 2009. Her husband had been captured by the Lankan army.

The protagonist’s agony has been detailed in all its stark brutality in a movie which also explores the horrid plight of hundreds of women desperately searching for their missing husbands. There is a lot of real footage with recreated sequences.

The documentary was ready in 2015, but it took years for Xavier to get an Indian censor certificate. Exhibition in Sri Lanka is out of the question. Now armed with Indian rights, Xavier’s search for a distributor has begun. There is none to be seen even on the horizon, for theatres know that they will receive threats from fringe groups once a release date is announced. No cinema is willing to see vandalism on its premises.

Another fiery filmmaking activist is Leena Manimekalai. In 2003, she began making documentaries, and it was one such project which took her to Dhanushkodi – on the island of Rameswaram – that was wiped out during a severe cyclone in the early 1960s.

“I thought I would do a documentary on Rosemary, a character who appears in my fiction feature, Sengadal (2011)”, Manimekalai told me in the course of a chat in Chennai. “I began my project in 2009 – the year the 30-year ethnic war in Sri Lanka ended. I had been a part of the Tamil resistance movement in Chennai. I will call myself pro-Tamil, but not pro-LTTE. So you find yourself in a no-man’s land, and you are at once seen as an enemy.”

This is one reason why Sengadal or Dead Sea attracted problems. “But I was fascinated by the stories of Sri Lankan Tamils who had suffered at the hands of both the country’s predominantly Sinhala military and the dictatorial attitude of the LTTE. One of them, Rosemary, was the widow of a Tamil fishermen who was killed by the Sri Lankan Navy. She then landed in the refugee camp at Dhanushkodi. There are 300 families there even today. And Rosemary helped me discover the distraught families. When I found that each one of them had a story to say, I decided that I must cross over to the realm of fiction to narrate something powerful. Sengadal happened,” Manimekalai said.

She had a massive issue with the Censor Board before Sengadal got a screening certificate. But, of course. She wondered why when there are so many movies on the Nazis and Jews, we should be so touchy about the Sri Lankan Tamils. A million of them were displaced during the war, and there are so many stories to be told about them.

Sengadal, Prasanna Vithanage’s With You Without You and Jaques Audiard’s Dheepan – which won the Palm dÓr last year at Cannes – are perhaps three of the very few films on this subject.

Manimekalai is planning two movies – one on the controversial Kerala poet, Kamala Das (whose conversion to Islam caused a lot of ill-feeling towards her), and the other titled Sunshine – a story about the tragedy of the cargo ship, Sun Sea, which sailed with 492 Sri Lankan Tamils from Thailand to Canada, but was not allowed to dock. A lot of people died. The year was 2010, and there was a lot of worldwide suspicion about Sri Lankans. It was assumed that most of them were LTTE rebels.

Be that as it may, Manimekalai seems all set to sail on one perilous journey after another, passionate as she is with opening the Pandora’s Box of heart-wrenching tales of simple suffering folks from an island nation.