Whose Sentiments Got Hurt Anyway?

There have been myriad responses to this release on social media, with some people highlighting Kali’s significance as a deity who rejects social norms & pressures. It is worth noting that Kali is often depicted with her tongue sticking out, which is interpreted as her rejecting the moralistic pressures of society and her mockery of the people who defend them without examining their own desires and shadow selves.

On the 2nd of July, Toronto-based poet and film-maker, Leena Manimekalai announced the launch of their new film ‘Kaali’ at the Aga Khan Museum. The film was announced as a part of the week-long Rhythms of Canada festival at the museum.

In the poster, a person with long hair and various adornments such as a crown and jewelry across their chest, seems to portray the blue-skinned deity, Kali. They are wearing prosthetic arms and are carrying accouterments like a trident and a sickle made of cardboard. In another of these arms is a rainbow flag (signifying the queer rights’ movement), while the person themself sips on a cigarette.

There have been myriad responses to this release on social media, with some people highlighting Kali’s significance as a deity who rejects social norms & pressures. It is worth noting that Kali is often depicted with her tongue sticking out, which is interpreted as her rejecting the moralistic pressures of society and her mockery of the people who defend them without examining their own desires and shadow selves.

Others, however, issued threats against Manimekalai, who was born in Tamil Nadu. For instance, Saraswathi, who is the leader of a Hindutva group in Tamil Nadu, Sashti Sena Hindu Makkal Katchi, threatened to ‘bash up’ Manimekalai with slippers via a viral video, if the latter didn’t take the poster down in 4 days’ time.

Saraswathi’s video went viral around the 5th of July and the Selvapuram police began their investigations into the threat soon after, ending in Saraswathi’s arrest.

Several complaints have also been filed with the police, demanding punitive action against Manimekalai, in various parts of the country. For instance, the Hindu Suraksha Manch and the United Trust of Assam have filed an FIR in Dispur, Assam.

The Indian High Commission too urged Canadian authorities to take the promotional material down, showing how the State’s solidarity often takes the form of enforcing respectability politics, instead of encouraging democratic discourse through free speech and media expression. Following this, the Aga Khan Museum has apologised for ‘hurting religious sentiments’.

Ironically, this reminds me of that Dabur Fem ad that tried to position itself as inclusive by portraying a queer couple engaged in the rites of Karwa Chauth. While several in the community welcomed this, even as others (including myself) rejected it as an attempt to rainbow-wash casteist and colorist practices as queer-friendly, the brand itself took the video down after Hindutva advocates complained about hurt religious sentiments.

The moral of the story to me is that positioning ourselves as ‘well-behaved queers’ will never earn us the liberation nor the validation that we so desperately seek from a society that espouses values that reject and alienate us in systemic ways.

In a display of misogynistic and queerphobic algorithmic bias, Twitter too took down the poster, prompting Manimekalai to ask: “Will Twitter withhold the tweets of the 200000 hate mongers?”

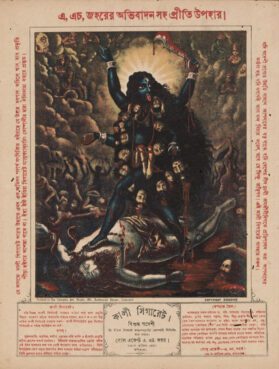

In response to the Hindutva-led reprimand of Manimekalai’s work and related promo material, Art Historian and Associate Professor at UC Berkeley, Sugata Ray, shared a lithographic print from the collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The print was a wrapper for cigarettes manufactured as part of the Swadeshi Movement (that boycotted foreign-made/branded goods as part of India’s fight against British imperialism).

Ray translated a few lines from the label as saying: If you care to improve the manufacture of swadeshi [national} products, if the welfare of the nation’s poor laborers is your concern, if you have a sense of good and bad, then O Hindu brothers, smoke these Kali cigarettes.

Soon after, an anti-caste Twitter user also asked if the famous Mangalore Ganesh Beedis will also be re-branded in the face of the imposition of Brahmnical values on various deities that have been part of various regional cultures and pagan groups in the Indian subcontinent.

Which begs the question: Whose Sentiments were hurt anyway? And whose sentiments do we care about? Art may not be an imitation of life in many ways, but its censorship certainly seems to be.

Celebrating the Plurality of Hindu Iconography & Tradition: In Defense of Leena Manimekalai

Hindus for Human Rights (HfHR) stands in unequivocal solidarity with filmmaker Leena Manimekalai, who has faced a barrage of threats and censorship for the poster advertising her upcoming documentary “Kaali,” which shows Goddess Kali smoking a cigarette and holding a pride flag. This poster has upset a subset of Hindus who seem unaware not only of the cultural practices of those who worship Kali, but of the incredible diversity inherent to Hindu traditions more broadly.

The true inner strength of Hindu religious traditions is that different communities have found spiritual inspiration in different ways. It is common in many parts of India for devotees of Kali to offer alcohol and meat as naivedyam (food offerings)—including at Kolkata’s Kalighat temple, which is one of the 51 holiest sites for Shakta Hindus. At the Viralimalai Temple in Tamil Nadu, cigars are offered to Lord Murugan. These practices are part and parcel of a diverse Hindu tradition, and Manimekalai has every right to explore these traditions through her art. Furthermore, many LGBTQ+ Hindus look to our traditions and sacred iconography as affirming their own dignity and identities, and the pride flag that Kali holds in the film poster is a way of acknowledging the deity’s meaningfulness to LGBTQ+ Hindus.

Furthermore, it is deeply troubling that the Aga Khan Museum and the Toronto Metropolitan University have apologized for collaborating with Manimekalai and revoked her opportunity to showcase her work. Twitter has also made the unconscionable decision to take down the image of her film’s poster. In kowtowing to the Indian government’s unreasonable demands for censorship, these institutions have betrayed the basic democratic right to freedom of expression while giving power to Hindu nationalists who seek to silence critics and artists.

As Hindus who believe in freedom of expression, the diversity and plurality inherent to Hindu traditions, and the sanctity of Mahakali, we fully support Leena Manimekalai and call on our fellow Hindus to stop all hateful threats and trolling. The Indian government is on an overt mission to make India a Hindu nation, and an integral part of this mission is a sustained effort to present Hinduism as a homogenized monolith. The world must not support this dangerous endeavor.

#Freedomofexpression -leenamanimekalai

To Leena Manimekalai

In a very holy land

In a very pious place

One hundred thirty crore people live

Sensitive, religious, courageous and non-sensuous.

We get hurt

And rightly so

When a polymorph smokes

And a strange man named Zubair

Says the truth

We are very decent people

We kiss in private

We kill in public.

We worship our goddesses.

We are fine with female infanticide

We are very tolerant

No one ever has been lynched here

for their names!

We are champions of freedom of speech!

We never celebrate violence.

Three days of peace conclave happened

In Haridwar

Under the holy presence of some

Holy men

No one has called for genocide there.

We, one hundred and thirty crore people

are very soft-hearted,

You must agree, Leena!

We boo our girls for being a lesbian

and we are the highest dowry payer!

This is the story of a noble country

You must understand, Leena!

How dare you, Leena!

How can your goddess work in a pride march!

About the poem: This poem is in solidarity with Leena Manimekalai who is getting a lot of flak for the poster of her movie.

Moumita Alam is a poet from West Bengal. Her poetry collection The Musings of the Dark is available on Amazon

My Kali is queer: Resisting the homogenization of Hinduism

Manimekalai calls “Kaali” a “performance documentary” — a personal and poetic meditation on the female divine. In a six-minute excerpt shown at a multimedia exhibition in Toronto last week, Mother Kali, Hinduism’s powerful goddess of death and the end of time, wanders through a pride festival in Toronto at night. She observes groups of people out on the town, takes a subway ride, stops in a bar. People take selfies with her. In the last frame, she is on a park bench where a man gives her a cigarette. The poster for the film shows the goddess smoking a cigarette and holding a pride flag.

The Aga Khan Museum and Toronto Metropolitan University caved in to pressure from the Indian government and issued apologies for screening the film. Twitter removed Manimekalai’s tweet showing the film’s poster. Manimekalai is wanted for arrest for “hurting religious feelings” in Assam, Uttarakhand, Haridwar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and several other states and has received numerous death and rape threats.

In an email Manimekalai said the controversy had made it impossible for her to return to India. “My safety is a big question mark now and I feel totally derailed to be honest. But I don’t want to bow down, and so I’m fighting with full power.”

Manimekalai comes from a South Indian community that worships the Goddess Kali as “a pagan goddess” who “eats meat cooked in goat’s blood, drinks arrack, smokes and dances wild,” the filmmaker told The Guardian.

Manimekalai, who identifies as bisexual, says, “My Kali is queer. She is a free spirit. She spits at the patriarchy. She dismantles Hindutva. She destroys capitalism. She embraces everyone with all her thousand hands.”

Someone unfamiliar with Hinduism might say Hindus are justified in their outrage. It’s important to understand, however, that the film and its poster are in line with a long tradition of diversity of Hindu practice and belief and immense personal freedom in one’s relationship with the divine.

An Indian member of parliament, Mahua Moitra, defended the film, saying, “To me, Kali is a meat-eating, alcohol-accepting goddess. I am a Kali worshipper. I am not afraid of anything. Not your goons. Not your police. And most certainly not your trolls.” Moitra is now facing criminal charges, too.

Kali first appeared in Indian culture as an Indigenous deity before being absorbed into the Brahminical traditions and Sanskrit texts in the present-day form “as a dangerous, blood-loving battle queen.” Hindu Goddesses are at the same time fierce warriors against evil and injustice and unconditionally loving and protective, and Kali’s devotees consider her the Divine Mother of all humanity.

Neither cigarettes nor queer pride is forbidden in Hinduism. Hinduism is historically very open toward sex and sexual difference. Innumerable stories in Hindu Scriptures tell of same-sex relationships, children born of same-sex relationships and characters — some of them gods — who are gay, queer or trans.

The South Indian Goddess Mariamman is often offered alcohol, and animals are sacrificed for her. The Guyanese “Madrassi” community comprises Hindus who worship Devi (the Mother Goddess) in all her forms, particularly Mariamman and Kateri Amma. “We firmly believe that devotion to Amma is subjective, and she comes to each of us in a unique way,” Vijah Ramjattan, president and founder of the United Madrassi Association in New York, told me. The community’s first Madrassi Day parade in 2017 featured an LGBTQ artist and dancer, Zaman, perform as the goddess Sundari.

‘Kali Cigarettes’ advertisement, Calcutta, India, circa 1885-90, Lithograph. Image courtesy British Museum

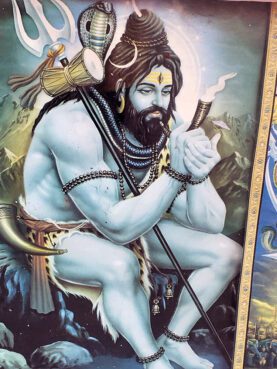

Hindu deities smoke, drink, get high and sometimes eat meat. It is very common for alcohol, meat and even cigarettes to be offered to deities, particularly Kali. As the writer Shuddhabrata Sengupta explains, in the late 19th century, a Kali brand of cigarettes was produced in Calcutta.

One advertisement read, ‘If you care for the development of ‘svadeshi’ [homegrown Indian] products, if you feel responsible for the poor, miserable, working people of this land, if you can truly distinguish between good and evil, then, o Hindu brothers, you must use these ‘Kali’ cigarettes!”

Walking through the narrow labyrinthine lanes of Varanasi, one of the holiest Hindu cities, it’s hard to miss the government-run “bhang” stands selling cannabis in the form of cookies and cakes, or as a drink. Most holy men in the city take bhang, local swamis told me, to deepen the experience of meditation and communion with God. Drugs have been part of Hinduism since prehistory; Lord Soma, the Vedic god of healing and plants, is named for a hallucinogenic which was offered to god and drunk by priests.

The extreme and egregious reaction to “Kaali,” the film, and its poster denies the Hindu idea that we all have tendencies towards goodness (satva), passion (rajas) and lethargy (tamas) and that our job is to ensure that the best parts of us win. We are allowed our mistakes because even the gods err.

And gods are everywhere: I grew up with my gods and goddesses on everything around me: my lunchbox and water bottle, clothes, vehicles, toys, movies and movie posters. We were taught to think of god in very intimate ways: Our parents and teachers were god, but so were spouses and lovers. I was called Krishna in my family because my mother and her sister were both mother to me, and Krishna, too, had two mothers. A friend told me his uncle was called Krishna because he had a wife and a mistress; Krishna, too, is known for having several wives and lovers.

An image of Lord Shiva lighting a chillum at Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi, India. Photo by Sunita Viswanath

I always appreciated this intimacy Hindus have with the divine that allows us to choose a deity for our devotions, to shape that deity according to our own desires. We come to the god of our choice as we are, and god welcomes us.

The violence and misogyny Manimekalai is facing is unconscionable, but the larger issue for Hindus is that her critics are bent on creating a homogenized Hinduism robbed of its glorious diversity. If there is a story of injustice behind every deity in India, the injustice today is that the deities themselves are being constrained, reduced, strangled. This homogenization favors Brahminical and Sanskritized texts and practices and erases the ways that non-Brahmin communities worship.

But the two issues are essentially the same: This homogenization favors male brutality. The Hindu nationalist version of the god Rama is warring, angry, with no Sita, his female companion, by his side. The Hindutva Hanuman is blood-red and furious, instead of the embodiment of love and sacrifice. Meanwhile they whitewash Kaali of everything that makes her fierce.

In the impassioned words of Moitra, “Neither Lord Ram nor Lord Hanuman solely belongs to the BJP,” she said, referring to India’s ruling Hindu nationalist party. “Has the party taken the lease of Hindu dharma? … [The BJP] is a party of outsiders that tried to impose its Hindutva politics but was snubbed by the electorate. BJP should not teach us how to worship Maa Kali.”

Kali, she concluded, “urges us all to resist the BJP’s attempt to “impose its agenda of Hindutva (Hindu nationalism) and thrusting its monolithic views” for the sake of the country.

This starts with giving a young filmmaker the right to express herself freely through her art.

(Sunita Viswanath is a co-founder and executive director of Hindus for Human Rights. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)